Victory Books

During World War II, the Victory Book Campaign hosted a nationwide book drive urging the American public to donate their favorite books to troops. Posters advertised the 1942 and 1943 drives, and approximately 10 million books were donated in 1942, with another 8 million in 1943. The main problem with these donations was that they were almost exclusively hardcover books. While these suited stationery troops—like POWs, shipbound GIs, and the convalescing—foot soldiers needed more portable reading materials.

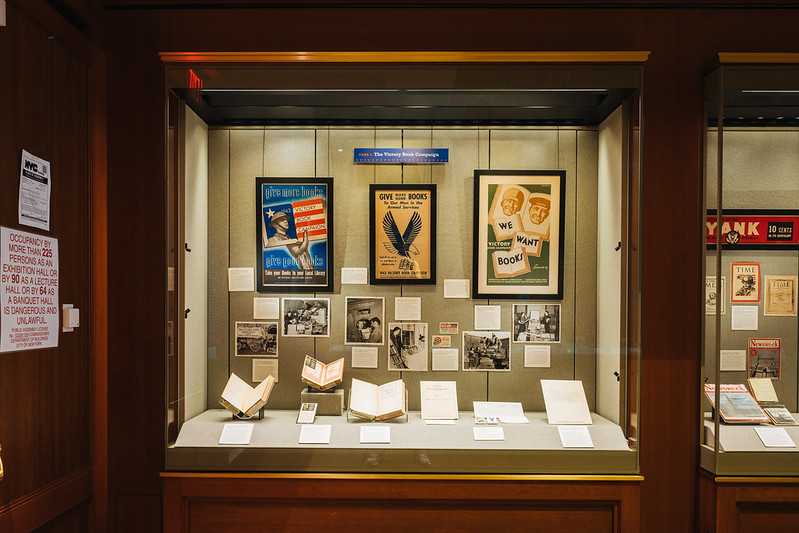

Give More Books, Give Good Books. Washington, D.C.: Office of War Information, 1943.

When the Victory Book Campaign was renewed in 1943, the public donated a large percentage of books that were unsuitable for troops. There were children’s books, antique tomes, cookbooks, and specimens in poor and soiled condition. Thus, the campaign began to advertise the need to give “good books.” The image of a young man wearing a helmet served as a reminder of the primary audience for the donations.

Give More Good Books to Our Men in the Armed Services. 1943.

This poster’s imagery of an eagle carrying a bundle of books evokes a powerful message of the role of books and ideas in a democracy. The Victory Book Campaign embraced this decal in its posters and other advertisements during the 1943 campaign.

We Want Books. C. B. Falls, 1942.

When the Victory Book Campaign commenced in January 1942, posters advertising the book drive appeared across the country—in train stations, grocery stores, public libraries, schools, courthouses, and office buildings. This poster by C.B. Falls was ubiquitous. By the summer of 1942, 10 million books were collected and donated to the military.

War Service Library Bookplate. 1917-18.

Rudyard Kipling. Plain Tales from the Hills. New York: Grosset & Dunlap Publishers, 1899.

B. Fall’s painting of a soldier carrying a towering pile of books was the most iconic image of the American Library Association’s book campaign during World War I. Though the 1917-1918 book drive inspired World War II’s Victory Book Campaign, the latter never adopted such a handsome bookplate to mark donated tomes.

John P. Marquand. So Little Time. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1943.

To ensure a good selection of books, the Victory Book Campaign solicited donations directly from publishers and leaders in the book industry. The Book-of-the-Month Club generously donated tens of thousands of popular titles to the armed forces. Here, a bookplate indicates that So Little Time was among the titles donated by the Book-of-the-Month Club in 1943.

Count Leo Tolstoy. War and Peace. New York: The Book League of America, undated.

A far cry from the beautiful bookplates the American Library Association provided during World War I, the Victory Book Campaign typically marked its donated books with a utilitarian, drab stamp. “Gift of the People of the United States through the Victory Book Campaign (A.L.A.—A.R.C.—U.S.O.) to the Armed Forces and Merchant Marine,” it stated. This book also happens to be stamped by the book’s recipient, the Ninth Service Command Library in Seattle, Washington.

St. Louis Public Service Co., Weekly Transportation Passes. February 15-21, 1942; January 17-23, 1943.

Across the country, the Victory Book Campaign was advertised by public transportation companies. Posters were hung inside buses and trains, and collection bins were located in most stations. In St. Louis, weekly bus passes were transformed into attractive reminders for the public to drop off books at libraries and high schools in the area. “More good books now needed for the men in service,” one ticket states.

Brooks. Detroit WWII Victory Book Campaign. Detroit: Detroit News, February 3, 1942.

Even children assisted the Victory Book Campaign. Pictured are two boy scouts collecting books in Detroit. The girl scouts and camp fire girls also undertook book collections. The efforts of young Americans made a considerable impact: one group collected 10,000 books during a single day’s door-to-door campaign. Aside from youth organizations, most public schools had book drops, and children regularly gathered books from home and their neighbors to donate at school.

Nagel. “First Load of 6,000 Books Leaves for Selfridge Field.” Detroit: Detroit News, February 3, 1942.

Like so many libraries across the country, the main branch of the Detroit Public Library undertook a massive effort to collect tens of thousands of books for the 1942 Victory Book Campaign. In a matter of weeks, over 6,000 books were collected at this library, alone. Here, the head librarian of the Detroit Public Library watches as boxes of books are transferred to Army custody.

Librarian with Book Truck. Fairmont, WV: Memphis Press-Scimitar, undated.

Books were especially appreciated in military hospitals at home and overseas. This photograph was taken at Kennedy General Hospital where Sgt. Hilbert Luplow, who was wounded in action in the Italian campaign, selected a book to “while away an otherwise long afternoon.” T/5 Mary Hawkins, who had worked as a librarian at Fairmont State College (in West Virginia) before joining the Women’s Army Corps, made daily rounds with her book truck to serve bedridden patients.

Sgt. Dick Hanley. “Ship Library,” Yank, the Army Weekly, undated.

At ports of embarkation, the Victory Book Campaign often provided crates of books so that troops could grab reading material for their weeks-long journey to a theater of war. Most ships also had their own libraries. Stocked with books purchased by the Army and Navy, as well as Victory Book Campaign donations, these libraries bragged of incredibly high circulation rates and a constant need for more books.

Carbon Copy of Letter from Eleanor Roosevelt to F. H. Osborn, April 7, 1942.

Some military officers did not approve of providing books and libraries to American troops. When Norman Cousins mentioned some of the hardships the Victory Book Campaign encountered with the Army, Eleanor Roosevelt wrote to Brigadier General Frederick Osborn to arrange a meeting. Osborn, who headed the Army’s “Special Services Division,” supervised library service. Mrs. Roosevelt endorsed Cousins’ belief that the Army needed a branch “to be run intelligently to provide books.”

Envelope with June 30, 1944, Victory Book Campaign Decorative Postmark.

Even the United States Postal Service helped spread the word about the Victory Book Campaign. Alongside the postage is an advertisement for the book drive, “Our Men Want Books, Send All You Can Today.” Curiously, the Victory Book Campaign ended in 1943; yet, this 1944 letter still reminds the public of the need to donate books.

“Our Men Want Books,” Victory Book Campaign Stamp, 1942-43.

“Give a MAN a Book He Can Read,” Stamp, undated.

To spread the message for the military’s need for books, the Victory Book Campaign turned to various publicity strategies. These decorative stamps were one promotional device.

“Manual for State and Local Directors.” New York: Victory Book Campaign, 1942.

This manual was circulated to librarians across the country to ensure that all understood the mission and purposes of the Victory Book Campaign. It provided tips on where to place collection boxes, the most desirable book genres for donation, national volunteer groups that could be relied upon for assistance, and publicity ideas. “Our boys want books” so let’s “keep ‘em reading,” the manual concludes.

Librarians with Stacks of Donated Books. June 20, 1943.

In total, over 18 million books were collected during the 1942-1943 Victory Book Campaigns. However, as this image shows, practically all donations were bulky, hardcover books. While hardcovers were suitable for stationary libraries, they were too large and heavy for foot soldiers to carry. The need for lightweight, portable books for troops overseas was the primary reason the Victory Book Campaign was discontinued in 1943.

A Nice “Haul” of Victory Books. New York: Acme Photography, March 7, 1943.

As donations to the Victory Book Campaign slowed during 1943, volunteers hatched novel schemes to attract attention to their cause. Here, a covered wagon makes its way down Fifth Avenue in New York City. The enormous banner strewn across the length of the carriage publicized the need for books, and the use of a horse-drawn wagon (rather than a motorized truck) conserved resources at a time when gasoline and rubber tires were being rationed.