Brendan W. Clark

I have always been inclined to collect: at an early age, I found a passion in milk bottles of a dairy that once existed near the site of my middle school (and was at one point among the youngest members, at the ripe old age of 11, of the National Association of Milk Bottle Collectors). At 13, I graduated to oil lamps, medicine bottles, and rusty tools, to name a few, but eventually found my way to the more enlightened world of books. Aside from “dabbling” in Georgian furniture, George III silver, seventeenth century French oil paintings, and Assyrian cylinder seals, books form the centerpiece of my collecting passions.

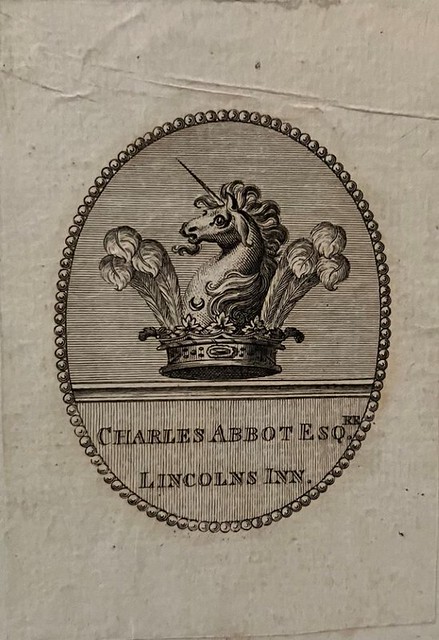

As a young collector, I was travelling in London and encountered a book that spoke to my classical education: a 1777 copy of Richard Bentley’s Dissertation on the Epistles of Phalaris, significant as one of the first translations of a classical commentaries in English, which were traditionally executed in German or French. This edition had another distinction: it contained a bookplate for “Charles Abbot, Esq., Lincoln’s Inn.” Out of curiosity, I queried the name, and learned that Abbot was no ordinary barrister—this was the Lord Colchester, Speaker of the House of Commons of Great Britain from 1802 to 1817. Colchester was a proponent of the book: indeed, he has been credited with originating the library of the House of Commons. This edition had traveled to the library of the Constitutional Club in London, a gift of Colchester’s son, sold off into the world upon the Club’s closure in the late 1970s.

I later discovered at the British Library that Colcester had a modest collection of books (several thousand volumes and some manuscripts), kept in his country home in Essex, that had been cataloged before being sold at auction after his death. My collecting, since then, has focused on recreating Colchester’s country library to come as close as possible to the library he amassed. His interests are broadly humanist, tinged with a clear sense of the imperial prospects Britain was contemplating during the Georgian period—early travelogues on Assyria, India, and travels closer to home; classical standards and works of literature from incunabula to his own time; key works of history, philosophy and treatises on the Anglican religion; and a smattering of works on law, drawing on Colchester’s training as a barrister and recipient of the Vinerian Scholarship at Oxford. As a law student (at William & Mary) and a former history major (at Trinity College in Hartford), many of my own intellectual passions and pursuits take me down the road Colchester carved in his selections of books.

Silius Italicus. De Bello Punico Iibri Septendecim. Antwerp: F. Asulanus, ed., Philippus Nutius, pub., 1567.

As one of the earlier texts in Colchester’s collection, this reflects his fascination with classical works and the conventional eighteenth-century English education he received at Christ Church, Oxford. Colchester had received the chancellor’s prize for his work in Latin verse at Oxford and this diminutive edition of the longest surviving poem on the Second Punic War reflects both a command of literature and a nuanced understanding of classical allusion and education. Indeed, many have noted the influence of Italicus in English poetic culture, especially the works of John Dryden and Alexander Pope. As a frequently assigned school text, the diminutive copy may well have been retained from Colchester’s school days. This edition was obtained from Christie’s at auction in April 2022 (with thanks to fellow Grolier member Rhiannon Knol who pushed for its inclusion in that auction).

Thomas Pennant. A Tour in Wales in 1773. Dublin: for Sleater, Potts, et al., 1779.

Colchester is fascinated with travel, both in the imperial colonies (and prospective colonies) of England that were under consideration as well as the regions and geography of England itself. In this case, Colchester selected a well-regarded text exploring different parts of Wales. Pennant was a collector in his own right (of art) and was interested as an author in travelling and writing compelling narratives of his time—he was, in the style of Gilbert White and Francis Grose, English naturalists and antiquarians, focused on describing his travels through his friendships with locals in the region. His travels took him, in this volume, to Chester, Oswestry, Llangollen, Mold, and Caerwys in Wales. There is some dispute among the ESTC over whether this edition was published as a pirated copy of an earlier edition.

William Robertson. An Historical Disquisition Concerning India. London: Cadell and Davies, 1809.

Colchester’s fascination focused especially on travel and the history of English colonies. While antedating the establishment of the Raj, England was firmly established in India through the reaches of the British East India Company. Written just a few years before the 1813 abolishment of the Company’s monopoly under the Charter Act, Robertson’s Historical Disquisition explores numerous facets of India’s history from ancient times and includes a substantial fold-out map. Robertson is especially fascinated with Indian history, imbued with the history of western connections, addressing Egyptian, Roman, and the historical passage to intercourse with India through the Cape of Good Hope. Robertson was purported to have been inspired to write his disquisition after reading Major James Rennell’s Memoir on the Map of Hindustan (1793) and drew, to some extent, on the monumental treatment of Rome by Gibbon. Restoration work on the binding (to reattach both the front and end boards) was executed by Natasha Herman at Redbone Bindery in the Netherlands.

Real Life In London, or the Rambles and Adventures of Bob Tallyho. London: Jones and Co., 1821.

Here, Colchester’s interest drifts closer to home, with a rousing literary exploration of London. Published in blue morroco, this is one volume of a two-volume set bound later and signed on the binding edge by notable binder Robert Riviere. Contrary to Colchester’s status, this text explored the intrigue of street life—drunks, squabbles, and rabblerousing. It is curious to wonder what his fascination may have been—or what escapes from the doldrums of aristocratic and political life—that this amusing volume may have entertained for Colchester. Containing numerous hand-colored illustrations by Alken, Dighton, Brooke, Rowlandson, and others. Often viewed as an imitation of Egan’s Life in London, the text is complicated for the bibliographer given the myriad variants which touch upon differences in plates and the placement of the plates within the text.

Nicholas Carlisle. The Gentlemen of His Majesty’s Most Honorable Privy Chamber. London: Payne & Foss, 1829.

Colchester’s fascination here—in contrast to Real Life in London—explores courtly intrigue and matters close to those with whom he associated. Obtained late in his life, just a few months before his death, this volume was likely bound in a tree calf binding after his death by Robert Riviere for a different owner. In his consideration Carlisle, himself a member of the Privy Chamber of George IV, reviews monarchs and their Privy Chambers from Henry VII to George IV and focuses especially on the men in the Privy Chamber and on the matters and concerns to which they attend on behalf of monarchs. In treating the subject comprehensively, he also addresses dress, the Chamber and Garden, and the role of the gentlemen of the Privy Chamber in coronations and in other events of royal significance.