Theology

Joacim di Fiore [attrib.]

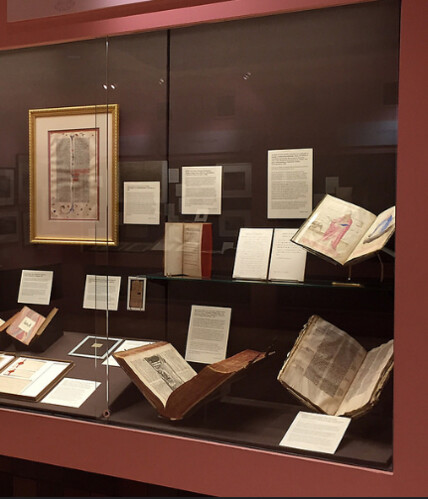

Vaticinia sive prophetiae et imagines summorum pontificum. Siena, workshop of Vecchietta, principally Benvenuto di Giovanni, 1447–1464. Illuminated manuscript on vellum, 9⅝ x 6⅞ in. Arts and Crafts binding by Katherine Adams, Worcestershire, 1905.

Provenance: Sydney Cockerell, with his manuscript annotations and separate notes discussing this work.

This is one of the first manuscripts or printed books that I acquired. It captured the thrill for someone like me, a neophyte with a curiosity that far exceeded my knowledge, to actually hold something like this in my hands and anticipate the many dozens of questions that would follow, many still unanswered.

This manuscript of sixteen leaves is comprised of two sets of riveting, fantasy-based images, which in their contempt and sarcasm came to represent the excesses and evils of the papacy during the Great Western Schism, and then foretell the future of a church ruled over by an angelic pope. Visually, it struck me at once as a mirror of the oppressive, fear-mongering tactics of the church. The bizarre, prophetic meanderings of the text has been attributed to the mystic Joachim di Fiore (b. Celico, c. 1132) and became the inspiration for radical movements among fourteenth-century Franciscans that led to excommunications and those movements being declared heretical.

The two groups of drawings are by two different artists, and in his manuscript notes in the endpapers, Sydney Cockerell refers to the first of these sets as the more compelling, noting that “Bernard Berenson regards these pictures as the work of an artist 'between Giovanni di Paolo and Vechietta.’”

Gifford Combs

Papyrus manuscript of a portion of the Gospel of John(Ch. 6:8–12, 17–22), ca. 250 CE, Aland no. P28.

This is, most probably, the oldest manuscript fragment of the New Testament in private hands. It was found in Egypt in the late nineteenth century, and is in a semi-uncial hand. The text, from the Gospel of John in the original Greek, tells the stories of two miracles: that of the loaves and fishes and of Jesus walking on water at Capernaeum.

For the past twenty-five years, I have been collecting manuscript fragments that illustrate the different scripts used throughout Europe to preserve and transmit knowledge through text from the ancient world to the invention of printing.

Christopher de Hamel

Testamentum Domini [The Last Will and Testament of Jesus], 5th c., in Greek, eastern Mediterranean (probably Constantinople).

I find tiny fragments of medieval manuscripts irresistible, often the smaller the better, and I have well over 600 of them, covering a huge range of texts. This is part of a small group of ancient parchment scraps that I bought in London in 2001. The clutch included some of the earliest Biblical fragments known from the eastern Empire, probably from Constantinople or possibly Antioch, as well as seventeen pieces of the celebrated fifth- to sixth-century Codex Gregorii, possibly once in the imperial library of Justinian the Great, emperor 527–65. This little fragment, hardly an inch high, is the smallest of all. It is by far the oldest extant piece of the Testamentum Domini, an early Christian apocryphal book of the New Testament, purporting to be the Will of Jesus, written in Greek and supposedly given by him to his disciples after the Resurrection. The text was hitherto reconstructed only from primitive translations into Syriac and other near eastern languages, none surviving from earlier than the eighth century. This fragment, in uncial script resembling the Codex Sinaiticus, is by 300 years the oldest witness to the text and is the only specimen of the Testamentum Domini in its original language. It has now been published in The Journal of Theological Studies 62, 2011, pp. 118–35.

H. George Fletcher

Commentarii in prophetias Osee, Ioel, Amos, Michaeae, et Nahum [Bible. Old Testament. Prophets. Commentaries.] Paris, 13th c. (latter half). Text manuscript on vellum, in Gothic minuscule.

Provenance: Julian Wolff.

Written by a single scribe in Gothic minuscule: two columns in black ink, rubricated, with marginalia, the Minor Prophets’ texts underlined in red; gatherings end with catchwords linking to the opening word or words of the following quire for correct sequence in binding. The marginalia are almost entirely by the scribe, in a smaller size of the text hand.

While losses include scattered leaves and one gathering each within Hosea and Amos, Nahum breaks off incomplete, and two additional Minor Prophets might be missing in their entirety, seventy-eight leaves survive. The manuscript, in other words, has been well loved over the many centuries.

One result of my distant academic specialty of Latin Palaeography is a modest collection of manuscripts, ranging in date from the late-eleventh to the twentieth century. This volume is a legacy from my staunch friend Julian Wolff, m.d. (1905–90; Grolier Club member 1975–88), a book collector from the 1930s who often attended auctions with John Fleming and whose achievements included his family’s own table at Lüchow’s.

Alexander Goren

Katholische Bibel. Das ist die ganze Heilige Schrift alten und neuen Testaments [Catholic Bible. The Scriptures, Old and New Testaments]. Nürnberg: Johann Joseph Fleischmann, 1763.

On a freezing night in Cambridge, Massachusetts in December 1958, at around 2:00 a.m., I was walking back to my room in Adams House after a feast of delicious scrambled eggs with a buttery, well-toasted English muffin at the Hayes-Bickford, on Massachusetts Avenue. (I had pulled an all-nighter in preparation for a final exam.) I passed an old bookstore and a big old book beckoned to me from the window display. In the darkness, I could only tell that it was a German bible. And it was the first time I felt: I must have this.

Following winter break, I went back to the bookstore to see if the object of my desire had waited for me. It had. I loved leafing through it and admiring the beautiful engravings. I also loved the old-book smell, the old binding and the metal clasps. I had to own it but it was marked at forty-five dollars (or twenty-five steak dinners at the Hasty Pudding Club). I figured a way to come up with the funds and acquired my first collector’s item.

This Roman Catholic Bible, with 212 engravings, has stayed with me for nearly the next sixty years, whether in New York City during graduate school; in Montreal, where I held my first jobs; Milan, where I had grown up; or London and Tel Aviv. For the last thirty years it has occupied a place of honor in my New York City library.

It is worth noting that I am not Catholic nor do I read German. But such is bibliophily.

Brian J. Morrison

Michael Servetus.

Christianismi Restitutio, Totius ecclesiae apostolicae est ad sua limina vocatio, in integrum restituta cognitione Dei, fidei Christi, iustificationis nostrae, regenerationis baptismi, et caenae domini manducationis. [Vienne, France: N.p.], 1553, [i.e., Nuremberg: Christoph Gottlieb von Murr, 1790].

This is the rare reprint of the book that cost Michael Servetus his life. Only three copies of the 1553 original are extant, the rest having been burned along with Servetus shortly after publication. A reprint edition was burned in London in 1723. Murr was successfully able to reprint the book in a small edition in 1790, now itself rare.

Writing the Restitutionof Christianity resulted in Servetus being labeled heretical by both the papacy and leaders of the Reformation in Geneva, in particular John Calvin. The nature of Servetus’s trial, sentencing and death has been the subject of religious tolerance debate for nearly 500 years; Locke, Voltaire and Jefferson have commented on Servetus and his tragic fate.

The story of the subject and author, the risk taken by the editor of this reprint and the scarcity of the present copy all make this book one of the highlights of my collection. I have found collecting the secondary literature on this subject equally fascinating.

Philip J. Pirages

Vellum manuscript leaf from the Summa collationum, sive Communiloquium. Catalonia, ca. 1400.

Written by the thirteenth-century Welsh Franciscan John of Wales, the work from which this leaf comes was meant to provide priests with basic information on how to lead a good life. Thus in sermons and conversation, they could instruct individuals about ethical conduct, reinforced by the work’s quoted texts (these texts comprise some 1,500 extracts from more than one hundred authors, many of them classical). As a practical handbook, most of the extant exemplars are carelessly written and intended for modest precincts. But we know that the book was owned more widely, perhaps most notably by fourteenth-century Spanish kings. Though there is no way of knowing if royal provenance was involved here, the decoration is so conspicuously grand that such a possibility is reasonable. The leaf comes from a very defective copy sold in 2003 at an auction where I was extraordinarily fortunate to outbid Barney Rosenthal.