Bibliography & Book History

Giuseppe Antonelli.

Ricerche bibliografiche sulle edizioni Ferraresi del secolo XV. Ferrara: Tipografia di Gaetano Bresciani, 1830.

Provenance: Franco Carresi, with his bookplate.

The origins of printing in Ferrara is a short story that focuses on eight printers and 121 books printed before 1501. Giuseppe Antonelli, one of the early bibliographer of printing in Ferrara, identifies 100 of the 121 books from the presses established there, with the remaining twenty-one added to the canon by the end of the century. One of the most interesting characteristics of Antonelli’s work is the three plates that illustrate twenty-three watermarks in the paper used by Ferrarese printers during the incunable period. Antonelli’s methods are quite sophisticated for the period and his work is still very useful when examining Ferrarese incunables.

I have been studying the history of printing in Ferrara for the last decade, and like the early Ferrarese imprints, bibliographical works on the subject do not often appear on the market. Edizioni Ferraresi is one of my favorite reference works and has been very useful in building my small but growing collection of books on Ferrara.

Marie Korey

Frances Mary Richardson Currer (1785–1861).

Catalogue of the Library at Eshton Hall, in the County of York. London: By Robert Triphook, 1820.

Frances Mary Richardson Currer built a library that placed her, in Dibdin’s words, “at THE HEAD of all female Collectors in Europe” (Reminiscences, 2:949). She greatly expanded the collection she inherited and published this catalogue for private distribution in 1820 and another in 1833. This copy bears a presentation inscription and includes additions in manuscript. Miss Currer hoped her library would remain at Eshton Hall but much of it was sold at auction in 1862. All three Currer catalogues, as well as some of her books, fit in quite nicely among the books about books I had acquired over the years with Richard Landon.

Jim Kuhn

William C. King, ed.

Portraits and Principles of the World’s Great Men and Women, With Practical Lessons on Successful Life by Over Fifty Leading Thinkers. Springfield: King-Richardson Co., 1899.

Issued in numerous bindings and at various price points, Portraits and Principles was sold door to door by book agents. Binding variants aside, collation of multiple copies reveals a range of other differences in text and illustration. Some were sold with tipped-in portraits and biographical sketches of the “Lights of Canada” or “Leading Boers.” But other, more elaborately planned and expensively produced variations exist. For instance, prohibitionist Wilbur F. Crafts is sometimes substituted for the “Great Reformers” portrait of abolitionist Frederick Douglass. How many variations exist? An ongoing collation project aims to find out.

George Ong

Rev. Thomas Frognall Dibdin (1776–1847).

The Bibliomania, or Book Madness. Containing Some Account of the History, Symptoms, and Cure of This Fatal Disease. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, and Orme, 1809 [i.e., New York: Privately printed for The Club of Odd Sticks, 1864]. Edition of five large paper, royal 4° copies printed on Whatman drawing paper; extra-illustrated. Binding by William Matthews in full blue morocco gilt extra.

Provenance: Francis Kettaneh, with his leather book label.

In Bibliomania (1809), Thomas Frognall Dibdin describes eight lustful symptoms found in the bibliomaniac. This copy satisfies at least half of them, being large paper, uncut, extra-illustrated, and unique. Its 180 portraits include engravings and India proofs of notables such as Dugdale, Erasmus, Shakespeare, Aldus, Boswell, and Dryden, as well as the distinguished bibliophiles John, Duke of Roxburghe, Topham Beauclerk, Hans Sloane, and others. And this copy’s large-paper margins are almost comically wide.

A reprint of the 1809 first edition, this is the one— and only—publication issued by the obscure Club of Odd Sticks, founded in New York in 1864 by Americana collector Francis Suydam Hoffman. The binder, William Matthews (1822–96), was not only highly accomplished in his craft but also a notable bibliophile in his own right; both he and Francis Kettaneh were members of the Grolier Club.

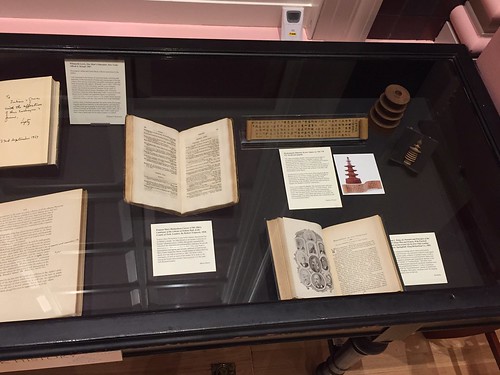

Hyakumantō Dhārāni.

Kyoto, Japan, [ca. 764–770 CE]. Scroll: 2¼ x 20½ in., pagoda: 8¼ x 3¼ in.

The oldest accurately datable, block printed-text on paper is recorded on miniature scrolls, or dhārāni (mantras), that Japanese Empress Shōtoku (718–770) commissioned to express her gratitude for the suppression of a rebellion by the Chancellor Emi no Oshikatsu and offer prayers for the future of the realm. However, her action also may have been an attempt to prove her piety after rumors had surfaced of an affair with the Buddhist monk Dōkyō.

A hollowed-out section of the tower of the pagoda holds this dhārāniscroll, one of four versions. Its design is thought to incorporate the Three Jewels of Buddhism: the finial representing the Buddha, the tower representing the Dharma (the teachings of the Buddha), and the base representing the Sangha (the Buddhist monastic community).

I have long sought this dhārāni. My miniature book collection integrates examples of book history—in small format—from the earliest cuneiform tablets to marvelous contemporary artist’s and fine press books, from four inches to less than a millimeter square! I often admire the beauty of my books, the craftsmanship of the artists and artisans who created them, and I’m awed by their history.

William P. Stoneman

Wilmarth Lewis.

One Man’s Education. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1967.

Provenance: Julian and Grace Boyd, with an inscription by the author.

I am interested in the history of American book collecting and especially in the movement of books and manuscripts in the last century from private collections into public institutions, and this book documents that subject. Wilmarth Lewis (1895–1979)was a major donor to Yale University and the Lewis Walpole Library has become a major research center for eighteenth-century studies and an essential resource for the study of Horace Walpole and his house, Strawberry Hill. Princeton University Librarian Julian Boyd and “Lefty” Lewis (as he was known to his friends) are important figures in a distinctly American study of seminal figures in the Anglo-American long eighteenth century and this copy records their close friendship.

Lewis was the author of a number of books, including Collector’s Progress (1951) and his Cambridge University Sandars Lecture, Horace Walpole’s Library (1957). He sponsored the Yale Editions of Horace Walpole’s Correspondence, which concluded in 1983 with its forty-eighth volume.

Lewis’s style is distinctly peculiar. He writes in the first person singular and plural and also in the third person, and sometime switches from one to another in successive sentences! He also refers to himself as Wilmarth, Lewis, WSL, Lewie, and Lefty. I enjoy owning this book immensely and I wish I could report that it was a good read; for its subject matter it is indeed.

G. Thomas Tanselle

Sir Thomas Browne.

Bound page proofs for Urne Buriall and The Garden of Cyrus. Edited with an introduction by John Carter. Printed by the Curwen Press. London: Cassell and Co., 1932.

Provenance: John Carter, with his manuscript corrections and revisions; then John Sparrow, with his signature.

Labeled in John Carter's hand “2nd proof corrected” on the half-title and “final proof” on the divisional title for “The Garden of Cyrus.” Carter entered fourteen revisions on five pages of his introduction and nineteen corrections on eleven pages of the text of “Urne Buriall.” One of the revisions is the addition to the acknowledgments of the name of John Sparrow (collector, essayist, and warden of All Souls College), and this set of proofs is from Sparrow's library. His signature and note “d.d. editor” (that is, “given as a gift by the editor”) are on the front free endpaper. These proofs (which consist of the letterpress only and do not include Paul Nash's illustrations) document a stage in the production history of a book generally regarded as one of the high spots of twentieth-century book design: it is, for example, called one of the Curwen Press's masterpieces by Martin Hutner and Jerry Kelly in A Century for the Century (Grolier Club, 1999). (Some of Carter's work for the second edition of 1958 is also documented here: Sparrow laid in a carbon typescript that Carter had sent him listing ten possible corrections to be made in the new edition.)

My extensive assemblage of Carter material is part of my collection of the major figures in nineteenth- and twentieth-century bibliographical history; and it holds a special place for me, not only because of the distinction of Carter's achievements, but also because I knew him during the last ten years of his life and remain grateful for his kindness and help.

Matthew McL. Young

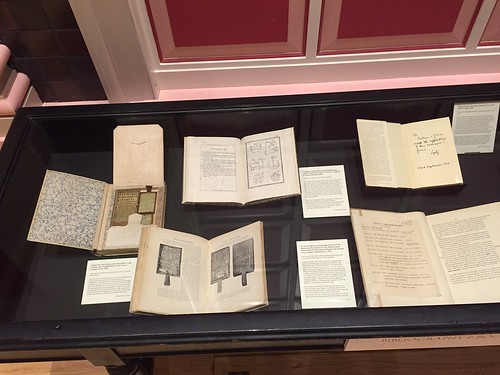

Andrew W. Tuer.

History of the Horn-Book, 2 vols. London: The Leadenhall Press; New York: C. Scribner’s Sons, 1896.

Provenance: Inscribed by the author, with A.N.S. to collector Robert White.

This was one of my first discoveries from a press whose books delighted me, and about which I could find almost no information. I was inspired to research their history and output, resulting in my book Field & Tuer, the Leadenhall Press (Oak Knoll Press/British Library, 2010), as well as a large collection of books, ephemera, and correspondence. Andrew Tuer found and described 150 surviving hornbooks (an 1882 exhibition of all then known had managed to show only eight), and his study, though unsystematic, is still perhaps the best on the subject.