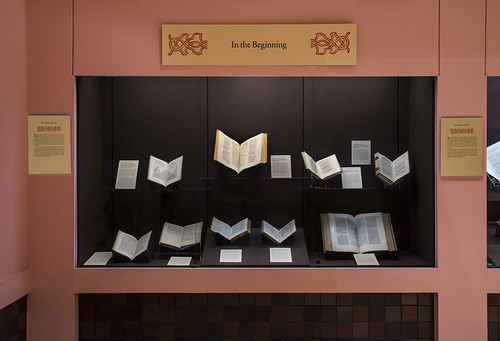

In the Beginning . . .

Manutius, Aldus. Musarum Panagyris.

[Venice: Baptista de Tortis, after March 1487 and before March 1491].

Although not issued by the Aldine Press, this small quarto comprising a mere seven printed leaves may be regarded as the “first Aldine,” as it provides the first printed evidence of Aldus’s arrival and existence in Venice. The text includes a letter to Catherine Pio, the mother of his young students Alberto and Leonello Pio, in which Aldus quotes Horace’s admiration for the Greek tongue.

To the Greeks the Muse gave genius and

Well-rounded speech. They sought nothing but glory.

You should turn these Greek models in your hands

Both day and night.

This slender volume may have served as an arrival announcement, or calling card of sorts, for the printing program that Aldus intended to undertake in Venice. His praise of Horace prefigures his desire to put the models of great literature into the hands of readers “both day and night.” This copy belonged to the Aldine bibliographer Antoine-Augustin Renouard (1765–1853), and is the only copy in North America.

From the collections of The Morgan Library & Museum.

The First Aldine

Constantine Lascaris.

Erotemata cum Interpretatione Latina. Venice: Aldus Manutius, 8 March 1495.

Constantine Lascaris (1434–1501) was a well-known Greek grammarian and teacher. His Erotemata (literally, “questions”) was first published in Milan in 1476. Aldus added his own Latin translation to this edition, the first dated publication of the Aldine Press. The book consists of a brief grammar followed by familiar passages of text (for example, the Lord’s Prayer and the Ave Maria) interleaved in Greek and Latin, so that students familiar with the Latin language could learn Greek through parallel reading. Publishing texts with interleaved translations remains a pedagogical approach to teaching languages today.

From the collection of T. Kimball Brooker

Swimming the Hellespont

Musaeus.

Opusculum de Herone & Leandro, Quod & in Latinam Linguam ad Verbum Tralatum Est. Venice: Aldus Manutius, [before November 1495 (Greek text) and 1497/98 (Latin text)].

As promised in the title, this short Greek poem on the star-crossed lovers Hero and Leander includes a word-for-word Latin translation by Aldus in order to foster the study of the Greek language through a more familiar tongue. Typographical evidence argues that the Greek text was printed earlier than the Latin text, with the two gatherings interleaved in most copies. Bound copies of only the Greek text are known to exist.

This is the first Aldine imprint to include woodcuts. On the left, Hero swims the Hellespont to be with his lover Leander. When (in the woodcut on the right) he collapses on the shore out of exhaustion, Leander, assuming Hero is dead, throws herself from the tower in grief. Bound in olive goatskin by Charles Lewis, and from the library of Beriah Botfield (1807–1863).

From the collection of T. Kimball Brooker.

The Student’s Bookshelf

Crastonus, Johannes.

Dictionarium Graecum. Venice: Aldus Manutius, December 1497.

This Greek dictionary of Johannes Crastonus (ca. 1420–ca. 1498) would have been an important tool for a student learning the Greek language. Crastonus’s dictionary is complemented by Aldus’s own Latin-Greek dictionary and a long preface to students on how to use the text. The volume was edited by Marcus Musurus (ca. 1470–1517), a frequent contributor to Aldine publications. Bound by Ridge & Storr of Grantham in red goatskin for Sir John Hayford Thorold (1773–1831) of Syston Park.

From the collection of G. Scott Clemons.

The First Greek Grammar Written in Latin

Valeriani, Urbano.

Institutiones Graecae Grammatices. Venice: Aldus Manutius, January 1497.

In order that readers of the Latin language might learn Greek, Aldus commissioned this grammar from the Franciscan friar Urbano Valeriani (ca. 1443–1524). Prior to this publication, Greek grammars were available only in Greek, and therefore only useful to students who already read the language. This book was in such demand that in 1499 Erasmus claimed he was unable to find a single copy for sale. Bound in contemporary blindstamped calf for the French humanist and bibliophile Benoît le Court (1500–1565).

From the collection of G. Scott Clemons.

Aldus’s Own Grammar

Manutius, Aldus.

Rudimenta Grammatices Latinae Linguae. Venice: Aldus Manutius, June 1501.

This is the second edition of Aldus’s own Latin grammar, the first having been printed in 1493 by Andrea Torresani, who was to become Aldus’s father-in-law in 1505. Although there were more Greek books to come, in 1501 Aldus began printing the celebrated editions of Latin literature in octavo format, so the issuance of this Latin grammar in the same year was not a coincidence. Once again we see Aldus’s intent to equip his audience with the tools needed to read his publications. The last gathering of the text, shown here, is one of Aldus’s rare attempts to introduce Hebrew typography and grammar into his printing program.

From the collection of T. Kimball Brooker.

Doing Greek While Doing Good

Poetae Christiani Veteres. Venice: Aldus Manutius, January 1501 – June 1502 – June 1504.

In his preface to volume I Aldus declares that he decided to print this collection of Christian poets so that students might learn Greek while studying sound doctrine, instead of relying on “pagan and lascivious poets.” The three volumes of this publication are usually found separately, and, as in this copy, individual texts are often ordered and bound to the specifications of a particular reader. This copy is rubricated throughout with red and blue initials, and heavily annotated in several contemporary hands.

From the collection of G. Scott Clemons.

In Contemporary Boards

Manutius, Aldus.

Institutionum Grammaticarum Libri Quatuor. Institutionum Grammaticarum Libri Quatuor. December 1514.

This third edition of Aldus’s own grammar (and the last published in his lifetime) retains the pedagogical approach of presenting familiar texts interlinearly in Greek and Latin. The book is open to the texts of the Lord’s Prayer, the Ave Maria, and the Salve Regina. The text concludes with four leaves of introduction to the Hebrew alphabet with several parallel passages in Latin, Greek, and Hebrew. Bound in contemporary quarter blind-ruled calf over wooden boards with metal clasps. The title is lettered on the fore-edge.

From the collection of G. Scott Clemons.

An Encyclopedia of the Ancient World

Suda. Venice: Aldus Manutius and Andrea Torresani, February 1514.

Suda, or the Suda Lexicon, is a 10th-century encyclopedia of the ancient world, preserving literary and historical information that does not survive elsewhere. As such, it would have formed an essential part of Aldus’s effort to preserve the patrimony of antiquity. Suda (or sometimes Suida) is not an author’s name, but instead derives from the Greek word σοῦδα, meaning “fortress” or “stronghold.” Bound in red goatskin by Charles Hering for George John, Lord Spencer (1758–1834), with the monogram of the John Rylands Library in Manchester stamped on both covers.

From the collection of G. Scott Clemons.